A look at how Lina Bo Bardi turned concrete into a medium for connection, culture, and everyday life by SURFACES REPORTER (SR).

When we chance upon a brutalist structure it comes across as a personality that is raw and honest. Hence it is quite a paradox that people have come to view them as symbols of bureaucracy and oppression. This view, however, took root because a lot of buildings commissioned for public use - including housing projects, government offices and educational institutions - made extensive use of brutalism. Brutalism at an architectural and cultural level has also been referenced as representing values of stoicism and heroism, which are inherently considered to be masculine traits.

In this supposed ecosystem of what often gets represented as patriarchal, Lina Bo Bardi attempted to alter the narrative with her approach. Consider this: if brutalism is Ying, Lina Bo Bardi added a good deal of “Yang” to the narrative by using raw concrete as a base for warm, communal spaces, blending the style with local culture and natural materials. In the present-day contemporary sense, she invoked Brazilian vibrancy in a corporate lingo obsessed with black tuxedo and stiff pencil skirts.

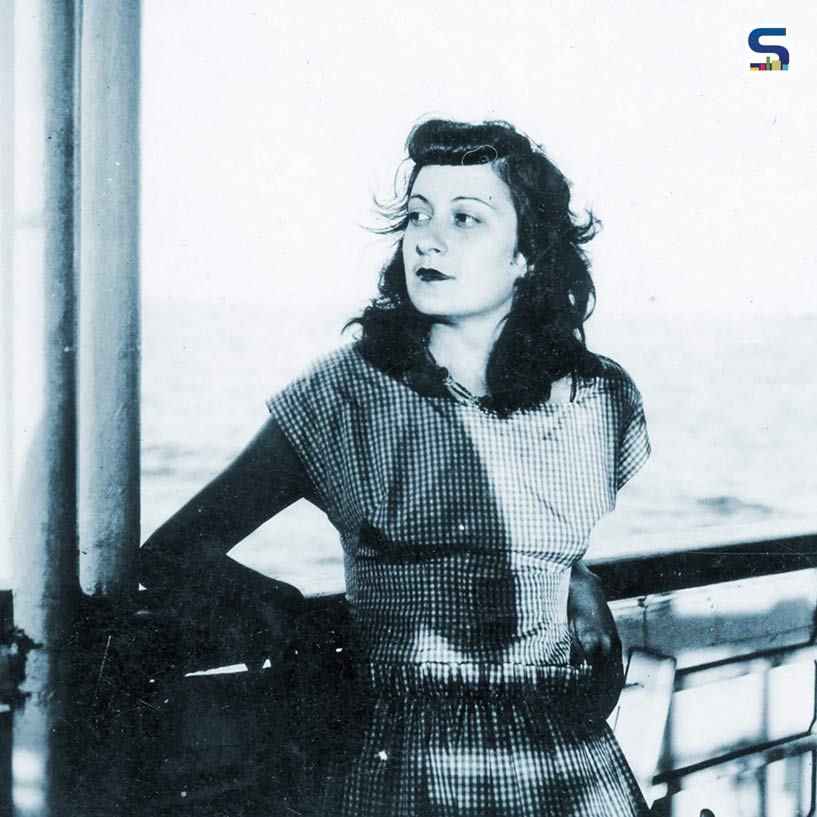

An Italian by birth, she married art critic and journalist Pietro Maria Bardi and moved to Brazil in 1946 where she re-established her practice - a country which would become the canvas of her humanist brutalism. In Italy, Lina was involved with the Italian Communist Party; this affiliation is also attributed to the destruction of her Italian office in an aerial bombing in 1943 by the Allied forces during World War II. Hence her attempt to humanize brutalism, which is quite popular in communist nations often cited for exhibiting totalitarian traits, is an interesting fact to ponder on.

The ideologues who have shaped design - as also the human mind - often align themselves with the image of god, an individual, or a set of collective minds who consider themselves harbingers of nature in the masculine or feminine form. In this setup, to alter or edit the idea is not an easy task. In addition to that, if you are a female born in a timeline where countries emerged out of world wars, it is certainly not an easy task. Despite the odds, Lina Bo Bardi managed to achieve this and add her name in the rare league of architects who added her own touch to an established architectural movement from within.

Brazil offered Lina her not just a new geography but a new cultural and social imagination - one she absorbed, celebrated, and amplified through her projects. It is here, where she pioneered an approach that softened brutalism without diluting its integrity, allowing the material to become not a symbol of power but a vessel for people and their everyday rituals.

Her first major project in Brazil, the Casa de Vidro (Glass House), stands as a quiet yet revolutionary thesis. Completed in 1951 and nestled within the lush forest of São Paulo, the house floats delicately on slender pilotis. While the transparency of modernism is evident, the building’s soul is unmistakably Brazilian. The forest becomes an extension of the living space, and the home responds to the terrain rather than dominating it. In an era where modernist homes often celebrated austerity, Lina introduced warmth, informality, and permeability, signalling that modernism could be intimate without losing its clarity.

Her first major project in Brazil, the Casa de Vidro (Glass House), stands as a quiet yet revolutionary thesis. Completed in 1951 and nestled within the lush forest of São Paulo, the house floats delicately on slender pilotis. While the transparency of modernism is evident, the building’s soul is unmistakably Brazilian. The forest becomes an extension of the living space, and the home responds to the terrain rather than dominating it. In an era where modernist homes often celebrated austerity, Lina introduced warmth, informality, and permeability, signalling that modernism could be intimate without losing its clarity.

If the Glass House was a whisper, MASP - São Paulo Museum of Art - was a proclamation. Completed in 1968, it is one of the most iconic brutalist structures in the world. Suspended by massive red concrete beams, the museum hovers above the ground, creating a vast open plaza underneath. This space - the “Free Span” - was not merely a structural decision but a democratic gesture. It functioned as a civic living room: a place for markets, protests, gatherings and performances. Inside, Lina’s exhibition design broke hierarchy. Artworks were displayed on crystal easels, allowing visitors to encounter them directly rather than through didactic, enclosed galleries. With MASP, she transformed the act of viewing art into an act of public participation.

If the Glass House was a whisper, MASP - São Paulo Museum of Art - was a proclamation. Completed in 1968, it is one of the most iconic brutalist structures in the world. Suspended by massive red concrete beams, the museum hovers above the ground, creating a vast open plaza underneath. This space - the “Free Span” - was not merely a structural decision but a democratic gesture. It functioned as a civic living room: a place for markets, protests, gatherings and performances. Inside, Lina’s exhibition design broke hierarchy. Artworks were displayed on crystal easels, allowing visitors to encounter them directly rather than through didactic, enclosed galleries. With MASP, she transformed the act of viewing art into an act of public participation.

Her ability to restore existing architecture with deep cultural sensitivity can be seen in Solar do Unhão in Salvador, Bahia. A 17th-century complex with a complicated socio-historical footprint, it was transformed by Lina into the Museum of Modern Art of Bahia. Instead of overwriting history, she preserved the textures of age, added a sweeping wooden staircase crafted without nails, and transformed the space into a thriving centre for Afro-Brazilian culture, craft, and education. Lina’s intervention here was less about modernizing and more about listening - allowing heritage to breathe and evolve rather than be sterilized.

Her ability to restore existing architecture with deep cultural sensitivity can be seen in Solar do Unhão in Salvador, Bahia. A 17th-century complex with a complicated socio-historical footprint, it was transformed by Lina into the Museum of Modern Art of Bahia. Instead of overwriting history, she preserved the textures of age, added a sweeping wooden staircase crafted without nails, and transformed the space into a thriving centre for Afro-Brazilian culture, craft, and education. Lina’s intervention here was less about modernizing and more about listening - allowing heritage to breathe and evolve rather than be sterilized.

.jpg) Yet it was SESC Pompeia that arguably became her manifesto of humanist brutalism. Converting a decommissioned factory into a cultural and recreational centre, Lina allowed the original industrial structures to remain, inserting walkways, bridges and courtyards that fostered movement, encounter, and spontaneity. The new concrete towers - bold, irregular, punctured by playful organic windows - became symbols of an architecture that was robust yet joyful. SESC Pompeia introduced the idea that culture, leisure, and recreation were not luxuries but civic rights. It was a place where anyone - from factory workers to students to elderly citizens - could swim, dance, rehearse, eat, rest, or simply linger.

Yet it was SESC Pompeia that arguably became her manifesto of humanist brutalism. Converting a decommissioned factory into a cultural and recreational centre, Lina allowed the original industrial structures to remain, inserting walkways, bridges and courtyards that fostered movement, encounter, and spontaneity. The new concrete towers - bold, irregular, punctured by playful organic windows - became symbols of an architecture that was robust yet joyful. SESC Pompeia introduced the idea that culture, leisure, and recreation were not luxuries but civic rights. It was a place where anyone - from factory workers to students to elderly citizens - could swim, dance, rehearse, eat, rest, or simply linger.

Across her works, her philosophy remained consistent: buildings must welcome people, invite improvisation, and reflect the energy of everyday life. She rejected elitism in both architecture and art. She resisted the cold, authoritarian modernism often associated with political ideologies. Instead, she embraced the sensorial, the communal, the improvised.

Her work is a reminder that architecture need not be a monument to authority; it can instead be a stage for humanity. Through glass, concrete, wood, and empty space, she offered Brazil - and the world - a new vocabulary for living together. Brutalism in her hands was not a command but a conversation.

Lina Bo Bardi, against the strict geometries of modernism and the patriarchal frameworks of her time, crafted spaces that pulsed with life. And in doing so, she secured her place not only in the history of architecture but in the broader narrative of cultural transformation - proving that even the hardest material can house the softest human truths.